The dashingly handsome “Mexican” John Marroquin was born in Texas, just across the border from old Mexico. He’d come to Wyoming with a trail herd in 1877 and worked for future Wyoming governor John Kendrick on the famed OW (located north of Lusk at the time) before starting with F.E. Addoms and R.F. Glover’s Four Jay Cattle Company in 1884.

Around 1888, the Keeline family made a deal on Addoms’ and Glover’s 4J outfit. George Keeline was a German immigrant who had changed his name from “Kuhnlein” and fought in the Civil War for the Union before homesteading in Iowa. Then he and his sons George, Frank and Oscar became the first men to run female cattle north of the Platte River (they established headquarters south of present-day Lusk and the town of Keeline is named for them).

In the purchase, along with one thousand head of cattle, 40 saddle horses and two teams of mules, the Keeline’s got the 4J’s horse camp on Caballo Creek in Campbell County – and the cowboy that Kendrick called “the best roper on the range.”

Mexican John moved to 4J headquarters where, from 1893 until 1910, the cowboys began cleaning out springs in Campbell County and built its first reservoir by damming Bonepile Creek (named for the large number of Indian ponies killed during a standoff) with horse-drawn scrapers.

By 1906, Mexican John was a top hand for the Keeline brothers, who were running 33,000 sheep and 30,000 head of cattle on Campbell County’s open range. They built a monstrous horse barn 60 by 80 feet that stalled 40 horses and held 150 tons of hay in its loft (it’s still visible from Highway 50, 16 miles south of Gillette). Mexican John eventually lived in a small room on the north side.

He was a busy cowboy. By 1893, Keeline’s employed more than 100 men and ran cattle and sheep over 250 square miles from the Black Hills to the Big Horns. By 1906, the Keelines’ 4J Ranch was running 30,000 cattle and 33,000 sheep. It shipped 120 railroad cars full of cattle every two weeks.

“It took two roundup wagons with up to 70 cowboys all summer and fall to brand, and they shipped two complete trainloads of cattle every two weeks,” remembered Harry’s daughter, Coramay Edelman. It reportedly cost the Keelines $12,000 a year to run those wagons over the ranch, which stretched from Lusk up almost to Buffalo.

After the Keelines’ final roundup on the diminishing open range in Campbell County in 1919, they sold the 4J holdings to Edward L. Fitch, who had also lived in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in the 1870s. Fitch kept Mexican John, while the 4J’s other foreman, George Amos, moved to Keelines’ newer spread. Amos died in 1929 after 43 years with the Keelines and left his estate to build the Campbell County Public Library.

Fitch ran a dance hall and saloon in Gillette for many years and served as town mayor in 1901-02.

But in 1923, with Fitch’s health failing, the Keelines took the ranch back and sold it again — to Adrian and Alice Mankin. They and their five sons and daughter were homesteading nearby.

This time, Mexican John would stay in his longtime home, the bunkhouse on the old 4J headquarters south of Gillette. That’s where he turned 75 in 1932 and 85 in ’42. Grand birthday celebrations were held at the old bunkhouse for each occasion, which drew many of the legendary open-range cowboys who settled the area, including George Keeline.

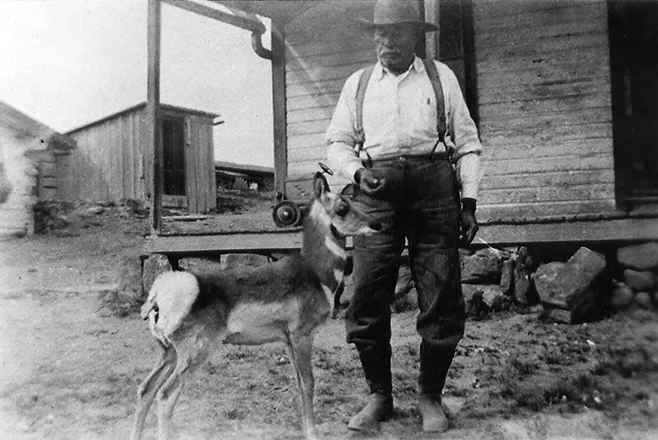

With his suspenders hooked to his neat jeans and his pants folded evenly above his boots, Mexican John was still handsome. When he was young, pretty women in Gillette could easily “separate him from his money,” as old-timers put it. He was an institution of sorts.

Known as the best roper in the Territory, John Marroquin was respected for his skill with a braided rope and a bull whip, both of which he handcrafted. He was recognized as part of a dying era, when cattle dominated the fenceless range, herded between Texas and Montana.

His tales would regale many, including the children who grew up on the ranch. For Adrian and Alice Mankin, who homesteaded less than a mile down Caballo Creek in 1920 and then bought Keelines’ 4J Ranch in 1923, Mexican John simply came with the purchase price.

“Old Harry Keeline, he kind of adopted him,” said 86-year-old Charles Dean Mankin. Charles Dean was born six years after his parents and grandparents (Adrian and Alice Mankin) arrived in Wyoming from Missouri on an immigrant rail car.

“He didn’t have any education,” recalled Charles Dean. “He couldn’t read. He finally got to where he could write his name.”

Each time the ranch changed hands, Mexican John stayed. He was the constant.

“Mr. Keeline used to come up and check on him. One time he went to the cemetery with Mexican John and said, ‘See, that piece of ground there? When you’re gone, that’s where I’m going to put you.’”

The site was where other old 4J cowboys and friends, George Amos and Tom Platt, are buried at Mount Pisgah Cemetery in Gillette.

“He said, ‘You and George will probably fight like hell, but I’m going to put you there,’” she recalled. “Mr. Keeline apparently felt an obligation to the gentleman for the past years. … He was just part of the household.”

Mexican John spent much of his life in and around the original Keeline barn — a monstrous and elaborate cow palace built in 1908 by cowhands — and the original log bunkhouse in Campbell County. The historic relic was built in 1896 as a dugout, and virtually the only changes made to it have been the addition of electricity and running water. The place was where the community cast their votes and it served as a stop-over for virtually every traveler headed to Buffalo, Douglas or Sundance. Another larger bunkhouse is next door, nearly as old as the original, and today houses hunters during the big-game season.

It was that original bunkhouse that housed Mexican John along with the Mankin family for many years.

A portion of the old cottonwood bunkhouse is still built into the earth and it’s possibly the oldest still-inhabited home in the county – or even the state. The floors slope because they’re built directly on the ground and the ceilings are only 6 feet tall. It was built by cowboys.

Mexican John was familiar with it all, including the rugged country west of the ranch that offers prime fishing and hunting. Just over the ridge is 21 Mile Butte, called that because it was a day’s travel to Gillette from that landmark.

Back then, many visitors would stop at the 4J on their way to Gillette. The road wasn’t paved for many years, but its name eventually changed from 4J Road to Wyoming Highway 50. And Mexican John was among the attractions.

“There was a big set of corrals right on the hill here,” Bill Mankin recalled. “There was a huge snubbing post in the center with a rut worn in deep from 60 years of snubbing broncs. They said they could run those horses to the gate and Mexican John would rope them with that nylon rope and jerk them down and never miss one.”

Bill, a team roper with his own championship trucks parked nearby, marveled at the skill. “That’s real hard to do,” he said.

“My dad used to talk about him a lot,” Betty added. “He was really good with a rope and a black snake (whip).”

Alice Lee remembers that, even as a young girl.

“He made black whips,” she said. “He used to go to the barn yard to practice. We watched him. It was the way he entertained himself.”

“I remember they had rawhide ropes … either four or five strands of rope, about the size of your finger,” Charles Dean added. “He’d cut it and then braid it. He was one of the best ropers in the country. He was, well, just a nice guy. … He went with the ranch.”

There are many stories about John Marroquin, known as “Mexican John.”

One was printed in the Council Bluffs Nonpareil in 1922 as he was in Omaha, Nebraska, for medical treatment. The Gillette News reprinted the article.

“John will take a fractious bronc anytime in preference to the newfangled street cars and refuses to trust his neck in one of them,” according to the story.

“He likes to see them rattle along with their human freight, for whose safety, John Marroquin offers up a whispered prayer every time a street car stops and starts.

“He failed to understand why people should ‘mill around like a scary herd when they can get so doggon much room and fresh air out on the prairies.’”

Another story is told by a former neighbor, Art Smelser, in his book, “The ‘Art’ of Being A Cowboy,” published in 2009: “Mexican John was the only name most of us ever knew him by,” Smelser wrote. “He was truly one of the old-time cowboys.

“… One time when I was about 4, my parents went to the 4J ranch to vote. “My dad said, ‘stay there and Mexican John will rope you.’ I stopped and watched while John whirled the loop once and sent it straight for me. The loop settled down over my head and he pulled it tight around my waist. I was surprised at how easy it seemed.”