Glenn E. Hanson was born in Newcastle, Wyoming on July 30, 1917, the youngest of three children born to Henrick and Roxie (Freel) Hanson. He was born in the “preacher’s house” near his grandparents’ home on the eastern edge of town. He spent the rest of his life on the family ranch where Henrick had homesteaded in 1908, the same year he and Roxie were married and built their 24-foot-square house, the first frame home in the neighborhood on the Cheyenne River, some 40 miles southwest of Newcastle.

He started school at five years of age, walking half a mile to a school that was built on skids and moved around to a location central to the neighborhood children attending. During his later grade school years, he helped his dad hand-milk as many as 17 cows before and after school; they would send the cream and butter with the mail carrier to town to market. He later attended and graduated high school in Newcastle, staying with his grandparents, walking about a mile to school wearing white shirts that his grandmother starched and ironed with a flat iron.

He was 15 years old, weighing 96 pounds when he graduated, quickly stretching up to six feet, two inches by the time he turned 18. As his siblings pursued higher education, he became his father’s and his Grandfather Jesse Freel’s mainstay ranch hand, annually trailing the Freel cattle singlehandedly from their summer range in the Limestone area of the Black Hills to the Hanson ranch on the Cheyenne River for the winter. He said the cows became used to where they were supposed to go and would string out for nearly a mile while he followed alongside, in the days when there were few fences to hinder them.

Glenn’s mother became the local postmistress at the homestead location in 1921 when the first rural mail delivery was established, and also opened a small store for the convenience of the neighborhood. The Postal Department in Denver combined the first three and the last three letters of her name to form “Roxson” Post Office. The mail was delivered and picked up on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays promptly, the same time of day each mail day.

During his growing-up years, with no established private fences, Glenn had to locate and drive their horses home in the springtime, including the farm teams. He told us many stories about wild rides to corral a large herd, including some genuinely wild stallions who instinctively knew how to escape the corralling. Also interesting was how colts would get tired from running, so their mothers would bump them along with their own shoulders, developing tremendous lung capacity in the young colts, making a horse with great traveling capacity in later life. Glenn owned such a horse, calling him “Tuffy,” and enjoyed riding him many years, many miles a day.

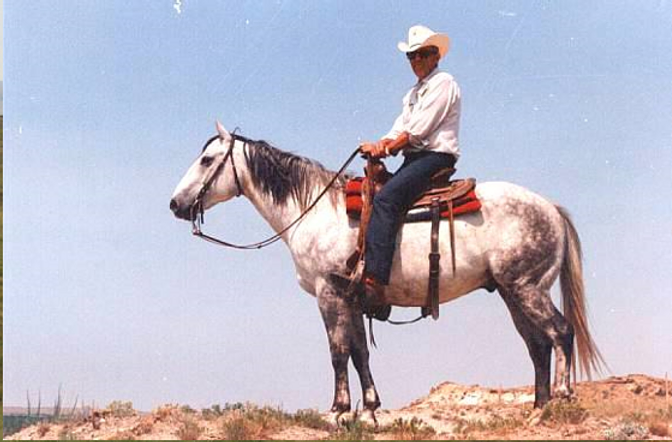

Throughout his life, Glenn’s favorite vantage point from which to see the country was between the ears of a good-traveling horse. Glenn was tall, with long legs and a short back, an advantage when it came to breaking broncs to ride, which he did a lot of, earning five dollars a head in the days when he just roped the bronc, tied him to a post in the center of the corral, saddled him, climbed aboard and “let ‘er rip!” When he began getting ten dollars per bronc, eh felt he’d hit the “big time!”

Glenn was 22 years of age when he married a neighbor girl who had stolen his heart and they were married. Phyllis was by his side for 68 years as wife, helper and mother to their five children, with no phone and no way to get help when he suffered a heart attack at the age of 37 with mowed hay down in the field, or when his thumb got mangled in a gearbox and he needed medical attention. She always did the “next necessary thing” that had to be done, with little thought for herself and no time for foolishness; she was his mainstay and an exemplary strength and loving example for the family and in the community. No matter what the time of day, anyone traveling by would be fed and cared for if they came to her door. The first summer after they were married, Glenn and Phyllis lived in a sheep wagon and Glenn herded sheep for a neighbor; he earned $50 a month and they paid their own expenses, the one time in his life that Glenn worked for wages. The summer was hot and Phyllis endured the heat by placing wet towels over herself for cooling, the only relief available.

Through the years, Glenn did anything he could do to earn a few more dollars in order to purchase another piece of ground adjacent to the original acres encompassing the homestead that he purchased from his dad in about 1948. Besides breaking broncs, he tracked coyotes, sometimes for miles, digging out their dens for the county bounty paid for each coyote, hauled cattle for others in his small straight-job truck with a stock rack, and finally started selling alfalfa seed from the meadows he and his dad had planted with teams of horses. That endeavor was the most lucrative and he devoted much of his life to flood-irrigating from the Cheyenne River and putting up the hay for winter feed prior to growing the seed crop each summer. To watch the water spreading out over the alfalfa fields gave him great satisfaction, as he knew when the hay would grow and the cattle would have the winter feed. With his creative methods and long days of hard work, he managed to enlarge the ranch some ten-fold.

Glenn and Phyllis always sought to encourage the neighborhood children to learn, starting a local 4-H Club and becoming leaders in livestock projects and homemaking projects, teaching livestock judging and square-dancing to further a sense of community in future generations. Phyllis also taught piano lessons to neighboring girls, furthering their enjoyment of everyday life in the country.

Glenn served on the local school board for many years, eventually initiating the building of a new permanent schoolhouse some four miles south of their ranch home, which was built by all the men in the neighborhood and eventually contained a separate room for two years of high school. All five of the Hanson children attended this school, the two eldest for ten years. During this time, Glenn drove the family’s car sixty miles to attend school board meetings in the evenings, getting home very late at night.

Glenn always arose very early in the mornings to begin cooking bacon and eggs for the family; Phyllis made the pancakes and the family got fed before making lunches and driving the four miles to school. His standard wake-up call for the ones sleeping upstairs was to call up the stairway that “People die in bed, don’t you know!”

The original homestead house was where Glenn and Phyllis lived, raised their family, building onto two sides of it and converting the front porch to a kitchen for more room as the family grew. The family has continued to call it home for five generations after it had been enlarged and remodeled some eight times to keep it comfortable and modern.

Glenn believed that good fences make good neighbors and taught his family to make the best use of time, believing that the “day’s half over” by 9:00 in the morning.

Glenn passed away in 2007, just short of his 90th birthday, Phyllis some three years later.