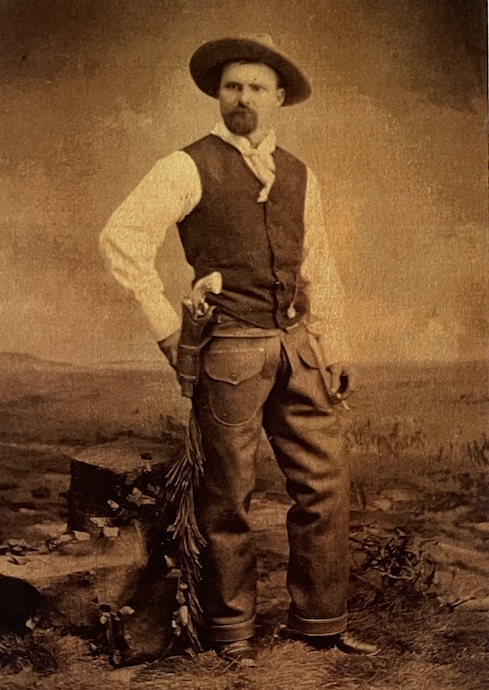

Lee Moore is one of Wyoming’s true range cowboys having made three trips from Texas to Wyoming with trail herds in the mid-1800s.

Moore grew up on the cattle ranges of central Texas and spent his life in the evolving world of the nineteenth-century livestock industry. Born on January 1, 1856, at Round Rock, Texas, he was the eldest child of John and Emily (Rody) Moore. His childhood unfolded in the communities of Round Rock, Taylor, Thrall, and Georgetown. By the age of ten he was already working—“repping,” as the Texans called it—for local cattle outfits. His own written reminiscences, later shared with the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association, described those formative years and the early lessons of the trail.

Moore made three major cattle drives from Texas to Wyoming, beginning in 1877. That first winter he camped at the site of what would become Douglas, after turning the herd loose on the north side of the North Platte River. The following winter, 1878–79, he and the trail boss stayed east of the present Ogallala Ranch, caring for the outfit’s horses. The cattle traveled under the O Bar O brand (0-0), and the Wyoming headquarters later became known as the H Bar O.

In January 1883, after a brief return to Texas, Moore married Amanda Thomas at Taylor. The couple moved back to Wyoming soon afterward, living first at Antelope Springs and then at the H Bar O headquarters, where their first child was born. Moore served as foreman of the H Bar O from 1883 until the outfit closed in 1887 following the catastrophic winter of 1886–87. When the ranching interests were sold to the Ogallala Land and Cattle Company of Nebraska, Moore stayed on for about a year under manager William C. Irvine.

By the late 1880s Moore had started assembling his own herd. His independence brought friction with the powerful Wyoming Stockgrowers Association, which blackballed him for “using the iron too liberally”—branding calves they believed belonged to the larger outfits. Despite their objections, his skills and knowledge of the country were indispensable. In 1888, the same year he was barred, he was nevertheless placed in charge of the roundup because no one else could handle the terrain, the men, and the work as effectively.

The great winter of 1886–87 had tested him severely. Moore and fellow cowboy Ollie Chambers stayed at the H O ranch, cutting firewood from corrals and fence posts when fuel ran out and rebuilding the ranch structures the following spring using saddle horses in place of a proper team.

As tensions escalated in the years leading up to the Johnson County War, Moore found himself frequently on the move. In 1892 he sent his family back to Texas for safety. He and his crew often traveled by night, hiding by day. During this period, he worked with two skilled ropers, brothers Antwine and Louie Bush—part Indian cowboys known across the ranges for their horsemanship. Moore himself was confident enough to wager that Antwine could tie down a steer with a clothesline. Rival outfits made their own wagers, but none challenged the Bush brothers’ skills on the open range.

Accusations of rustling continued to shadow Moore, fueled in part by lingering animosities within the Stockgrowers Association. At one point famed lawman Joe Lefors was allegedly hired to kill him. Though Lefors later claimed—under altered names—to have arrested “Lee Moon and his son,” Moore was acquitted of all charges, though the legal battle cost him heavily. According to Moore’s son, Moore once invited Lefors to dinner at a trail camp, then quietly saddled a horse and slipped away before Lefors realized his quarry was gone.

After 1892 the Moore family settled in Newcastle, where Moore continued ranching. When persistent conflicts forced him to sell out, the Wiker family purchased his Seven Cross-branded cattle. To shed the negative connotations of the brand—sometimes applied to calves in ways meant to frame small operators—the Wikers changed their mark to ZL.

In 1899 Moore moved to Lightning Creek and bought the Royston Ranch. A year later the Wikers followed, settling nearby. Around 1902 Moore acquired a house in town so his children could attend school. The families were close; several Moore and Wiker children attended school together, while Moore’s son Leroy, known as “Daddy Ock,” never returned to school after their Newcastle years.

Moore ran the Lightning Creek ranch until about 1909-10, when he sold it to Leroy. He then moved to Diamond, Wyoming. In the early 1920s he was appointed Secretary of the Wyoming Livestock Board, a position he held until 1927. That year he moved to the Ogallala Ranch at the request of his son. On February 7, 1928, after riding out for the morning as usual, Moore returned to the ranch store, tied his horse, walked inside, sat down, and quietly passed away. Amanda Moore survived him until March 4, 1937.

Among the many stories told of him, one of the most enduring is his all-night ride from Sundance to Douglas in 1887. After testifying in a horse-stealing case in Sundance, he rode out at 3:30 p.m., changed horses at a Spring Creek camp before dawn, and reached Douglas—150 miles away—by the time court convened the next morning. It was the kind of feat that defined him: steady, capable, and devoted to his work.

Across six decades in the cattle business, Lee Moore rose from a Texas boy with a sheepskin saddle to one of Wyoming’s respected old-time cowmen. His life mirrored the rise, evolution, and turmoil of the open-range era, and his stories—told in his own words and remembered by those who rode with him—remain a vivid record of the frontier cattle country he helped shape.