Joe Coykendall was born in Rand, Colorado on November 12, 1917. He grew up on a small ranch owned by his parents, Frank and Edna Coykendall. The family lost the ranch in the Great Depression. Eventually, around 1935, Frank Coykendall became ranch manager of the Joe Miller Land Company, Inc. (the “Miller Ranch”) and Joe began there as a ranch hand.

From the mid-1930’s until December 1941, Joe worked for a number of ranches in Albany and Laramie counties, including the Miller ranch.

One of his employers, a widow, had great confidence in him and they settled on an arrangement where he would continue to work for her and buy her ranch. They met with Laramie banker George Forbes, my grandfather, who, after one look at Joe Coykendall, told the widow that Joe was too young and unproven to be trusted. That was the only opportunity Joe ever had to own his own place.

Joe volunteered for the Army Air Corps within days after Pearl Harbor in 1941. He was sent to the Pacific where he saw action, including at Guadalcanal, the only battle he would ever speak of. He returned to the Miller ranch in 1946 and worked there continuously, first under his father until his father’s death in 1969, and then as the ranch manager until 1974.

Joe then worked on a Colorado horse ranch from 1974 until 1979, when he was hired to manage the Booth ranch, again in Albany County, Wyoming. He managed that ranch from 1979 until his retirement in 1991. Joe died on March 30, 2008.

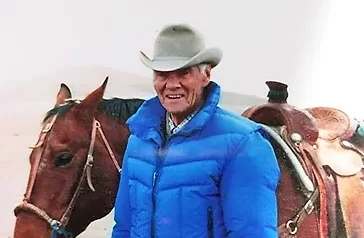

Joe was built like a telephone pole. He was over six feet tall. He always wore a cowboy hat and always smoked. Red Garretson referred to him as “High Pockets” and that was an apt description. His demeanor was gruff, and some called it “intimidating.” If you happened to run into him, you might have seen a creased face and a deadpan expression with a down-turned scowl. He referred to himself as a “miserable S.O.B.” But Pep Speiser describes it best when he stated that whatever Joe’s demeanor, he was nothing more than a “big marshmallow.” He was kind, honest, charitable (except when he played poker per Bob Sexton).

On behalf of the Miller Ranch, he was a part-sponsor of Little Britches Rodeo and volunteered in assisting with those events.

Tage Benson told me that when he was 12 or 13, Joe happened to see him trying to move cattle on the Forbes ranch with a horse that was not of the best quality. Within the week, Joe took Tage to the sale barn in Laramie and bought him a good horse. Within the next few days, Joe brought him a 1910 saddle which he has to this day.

Everyone I spoke with stated that they remembered Joe as a good neighbor. He helped all his neighbors, including the Forbes family, with branding, working cattle, shipping cattle and cattle drives. Jim and his wife, Martha, Jankowski referred to Joe as their “mentor” in learning the cattle business.

Martha stated that they knew they could always count on Joe for help. Gerald LeBeau stated that during Joe’s Miller Ranch years, Joe was a good neighbor who looked out for others and tried to help them if he could.

Joe’s sense of humor was near legendary.

Gerald LeBeau states that when he would call Joe to tell him that “600 or 800” cattle had come through the fence on to his property, Joewould respond, “How’s the grass?”

Joe always had two or more of his cattle dogs in his truck. One day while his truck was parked in front of New Method Laundry in Laramie, the dogs knocked the truck out of gear and it rolled into the street. When someone came and got him, he responded, “Did they [the dogs] hit anybody?” Joe began his day way before dawn and even if you were at a designated spot by the appointed hour (no later than 5:00 a.m. usually), you would be met with the scowl and asked why you were late. Gerald LeBeau stated that on one occasion, he got to the corrals where they were working cattle at 1:30 a.m. and part of the joy of that occasion was being able to tease Joe about his tardiness when he arrived at 4:30 a.m.

Nick Speiser stated that if you were driving with Joe and it had rained or snowed, you had to be careful about hitting the potholes because if you hit one, Joe would say, “You just ruined a cow’s drink.”

Martha Jankowski stated that the day after she was married and had moved to the ranch, Joe was at their house at the crack of dawn banging the door and asking if anyone was up.

Everyone spoke of Joe’s skills with cattle, horses and dogs. These were skills that were admired by my father, Jim Forbes, too, in his lifetime. Joe was an excellent horseman and dog trainer. He was a top roper and would often compete in the local rodeos in Valley Station and Saratoga. Most of the people I spoke with said that they learned a great deal about working cattle from Joe. He was unusual for his time in that he believed in working cattle slowly and without noise. If he heard someone make noise, he would bark, “They know you’re here.” All of his dogs were always quiet working cattle. Joe believed that cattle work went quicker when cattle were worked slowly, calmly and quietly.

Though he never owned his own cattle, he devoted great effort to the welfare and well-being of cattle. In spite of his joke about potholes, Joe did genuinely believe in the importance of proximity to water. According to Nick Speiser, who worked for Joe in his Booth Ranch years, Joe believed that cattle shouldn’t have to travel more than a mile for water. To that end, he witched wells. He observed cattle closely. He was quick to be able to point out an animal that was not feeling well.

Joe was a teacher, one of the best I ever had. Like others, I learned valuable lessons about horses, cattle and dogs from him. But an outing with Joe, was, in the end, always an education. He had stories about the remotest corners of Albany County, places where one cannot imagine that anything much would have happened. I was with him on one of these outings once when he stopped the truck in the middle of the range and pointed to a little monument. He told me to go out and look it. It was the grave of a seven-year child and it read, “We found her here.” And Joe had the story to go with it of how the child got lost in a blizzard looking for her father.

Joe had a deep affection for the ranching community. In addition to hearing stories of Albany County ranchers and homesteaders, outings with him were always an opportunity to meet with other ranching families. Even if we were working cattle, there was always time to stop, have coffee and socialize. What Joe instilled in me, overall, was a deep appreciation of how unique our ranching community was, how tenacious and independent people could be, while still being good neighbors and good stewards who knew the land and loved what they did, despite its hardships.

At the Harmony café, during Joe’s Booth Ranch years, there was a sign at a table at the window that read, “Joe’s place,” just a small example of how much others enjoyed his company.

Joe was not a religious man. He referred to Albany County as “God’s country,” an ironic comment, but a sincere one as well. Joe so loved ranch life and his contemporaries that I always wondered how it was that he was able to leave it to spend five years in a war. I can only speculate that those years are what made his career, the people and the land precious to him. He did not believe in heaven, but if he knew that some ten years beyond his death, people would still think of him and speak of him, he would have said that that was all the heaven he deserved.